Two and a Half Years Before the Mast: A Second View on the Hartnell Family - Part 1

Two and a half years ago, I wrote my very first Franklin Expedition-related post about John and Thomas Hartnell. For the most part, it was meant to be elementally biographical; a side use was as an on-hand compilation of virtually everything I knew about the Hartnell family up to that point. It was a very exciting thing for me, as I had never really taken my own turn in the realm of academia aside from class-assigned essays and the like. That post was a preliminary foray into something I ended up hardly being able to fathom. If I had known then how far that one little thread of research would taken me, I'm not sure what my reaction would have been—screaming, probably.

My intent isn't to bore anyone with a VH1-esque 'Where Are They Now?' recap, aside to say that since September of 2017, study of the Franklin Expedition has saturated my entire life. I can claim some incredible friendships (Alison!! Shannon!!!!) and had some fantastic adventures to some far-flung places. Where I lamented the distance between the U.S. and U.K., I finally bridged it this past January. Granted, the point of my research has temporarily shifted to studying the character and life of Lieutenant John Irving, but the Hartnell family has never strayed far from my mind.

At the time of writing the original post, I felt that my study of the Hartnells was thorough—wildly so, I perhaps thought with a little too much confidence. Again, I have no idea how I would have reacted to all of what I know now. However, I think it's probably for the best I had that confidence in the first place, otherwise I feel that I would have shied away from publishing it! The great thing is that once the floodgates are open, the deluge is fairly nonstop, even though the rate of flow may change over time. Sometimes, what I found amounted to a trickle in a drought; other times, it was an overwhelming flood of Biblical proportions. At risk of holding this out like a recipe blog recounting stories of childhood pets and mountain hiking before getting to the recipe for an omelette, I feel like I should cut to the chase:

I only knew a quarter of the Hartnells' lives. Maybe not even that.

One thing I've definitely learned in Franklin Expedition studies is there's no such thing as an open-and-shut case. Every theory comes with its own debates; people offer differing accounts or ideas, sometimes just for the sake of posing an argument and raising questions just to ask. One person—let alone a family—was no different. And here, I'll start at the beginning. (Also, for sake of length, this series is going to be divided into three parts. :D)

I really, really mean the beginning.

Like, 1789. Forty-eight years before John Hartnell's death.

We have to start with the senior Thomas Hartnell, born around 1789 in the now-extinct parish of Stoke Damerel in Devon. Stoke Damerel is now just called Stoke, located within the boundaries of Devonport (or Plymouth Dock) in Plymouth. There, on October 18th, 1789, Thomas Hartnell was baptized as the son of John and Martha Hartnell. John the eldest had been a local shipwright—an occupation that would be recurring in the family line. Thomas was the second oldest child of the Devon Hartnells, just a year younger than his older brother John (not to be confused with his grandfather, father, nephew, other nephew, or son). He had four younger siblings, including his sister closest in age, Mary Ann.

We'll see her again in a little bit.

Very little is known of Thomas Hartnell's life (aside from some interesting neighbors in the form of some of Lieutenant Edward Little's family, although I have no idea if the two families ever met or connected; still cool, though!) until 1807. By this time, Thomas, age 18, was apprenticed as a shipwright at Plymouth Dockyard under master shipwright Richard Odgers. By this point, his father was referred to as the "late" John Hartnell, and Thomas' older brother Charles signed his apprenticeship form on August 5th, 1807—including clauses against drinkin', dicein', marryin', and fornicatin'. I haven't been able to find what happened to the elder John Hartnell, or really what happened in the interim between 1807 and 1815, when Thomas Hartnell married Sarah Friar of Teynham, Kent.

Sarah Friar (or Frier, depending on the spelling) was baptized in Teynham on April 21st, 1793 to John and Susan (or Susannah) Friar. From what I've been able to find, Sarah was an only child in a quiet family, and aside from one civil suit against a John Friar of Kent for disorderly conduct (the charges were dropped and I'm not even sure it was the same John Friar), all seemed to be fairly calm for the Friar family.

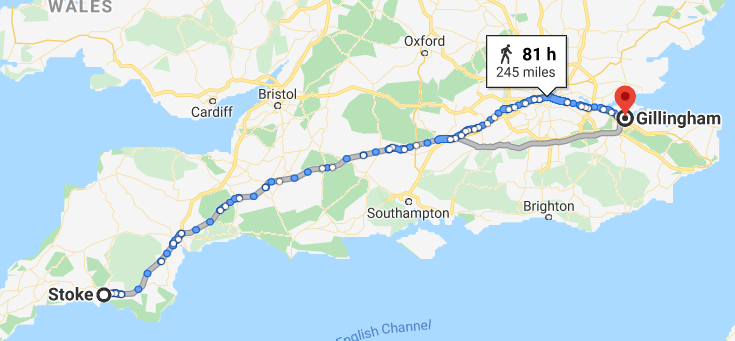

How Thomas and Sarah met, I'm not sure. At some point, Thomas was employed by Chatham Dockyard in what hadn't been a small move.

Wheeeee!

Admittedly, according to records, Chatham Dockyard was considerably more industrious than her Plymouth sister. I can't speak for the rate of pay, but something lured Thomas Hartnell to Chatham Dockyard's gate, and eventually to the Frindsbury church where he married Sarah Friar on October 9th, 1815. I also can't speak for the marital felicity or the undoubtedly charming life of a shipwright in Gillingham, but just shy of five years later, the couple had their first son.

John was baptized at St. Mary Magdalene Church in Gillingham on July 16th, 1820. I talked about this a bit on the first post, but combing through the records and comparing births and baptisms around the Gillingham, Brompton, Chatham, and Rochester areas yielded the general consensus that most working-class families waited around two months to baptize a newborn. The same held true for John's younger brother, Thomas, who was recorded on the family gravestone as being born on March 12th, 1822 and baptized on May 12th of that year.

Et voila! Happy birthday!

If the same holds true for John, his birthday might have been around May 16th, 1820 (

To this day, I'm still not one hundred percent sure what the relationship was like between the brothers, but undoubtedly they had some closeness in being only two years apart in age. After them, Sarah gave birth to a son named Charles, baptized on September 19th, 1824. However, Charles passed away on December 11th, 1825. Following him in birth order was Mary Ann, baptized September 17th, 1826. The second Charles Hartnell (it was still customary around this time and this area to use a name again after the death of an older sibling) was baptized June 1st, 1828. Finally, after a four year gap, Betsy was baptized January 22nd, 1832.

Defining the relationships between the Hartnell siblings is hard to do, considering they did write letters, but weren't avid about it. If they were, few letters have been immediately forthcoming out of any collections. But from what's been written by Sarah and Charles, there are a few facts that are apparent and documented. They help build up the world around the Hartnell family in surprisingly vivid color.

Not pictured: me freaking out because I love me some lych gates

In the original Hartnell history post, I tried to apply as much personal insight as I could; I write fiction more than anything, so it's kind of my nature to do so. However, I couldn't really apply it properly without seeing Gillingham myself. Granted, my glorious guide Abel was pretty amused that I was getting psyched about going to a small town in Kent, but hey! At least I was excited!

Going there made me understand a few things. The first was that, in reality, Gillingham hasn't changed that much since the Hartnells were growing up. I mean, yes, there are plenty of modern conveniences. Gillingham has a pretty fantastic set of parks, a gigantic Tesco, car dealerships, and pretty decent take-out restaurants. It's more like the nature of Gillingham doesn't seem so different. While we were walking around Exmouth Road (I'll get to that one in a minute, too), Abel and I met a very nice couple that started off talking to us about the local stray cats that are something of celebrities nearby, and then went on to talking about Gillingham, St. Mary Magdalene's, and the area in general. There was such a level of excitement in them that was practically infectious, and they even asked us to stop by the church for coffee on Friday (I was headed to York by then otherwise I so would have). The entire time, I wondered if that same tight-knit neighbor feeling applied to that street almost two hundred years prior, and it made me feel warm and fuzzy just to think about. It turns out, Sarah Hartnell was able to confirm it.

Earlier that day, we'd also gone to the Ship Inn, a little nautical-themed pub set in a building established in 1792. Poking around, I found that this pub wasn't too far away from a pub that had existed in the Hartnells' day, known as the Four Brothers (since demolished to make way for housing), just a short walk away from St. Mary Magdalene's.

Jury's out on who in the family might have enjoyed it

Sitting in the pub, watching families eat Sunday roast and listening to talking and singing, it really did give a sense of something, like you could easily put one of the Hartnells there and they wouldn't have seemed out of place.

It was even more vivid at the church itself. We weren't able to go in at the time (happy Sunday?), but even just walking the grounds while listening to the cooing doves and chattering magpies made it all feel right. I felt like I could safely set the Hartnells on their stage in the town that few of them ever strayed far from.

Another thing I came to understand is the role the River Medway might have had in their lives. Gillingham is situated on a little more of a height than I thought, and the town itself sort of slides down to the river on a slightly precarious slant that I'm sure has been tamed with construction over the years. But standing at St. Mary Magdalene's or Exmouth Road or any route in between, the presence of the river is constant. Consulting maps drawn up around the Hartnell era yields a vision of a town bound to a river in every respect—orchards grew on the banks and relied on the water, fishermen plied the waters around the marshes, people dug through the muddy foreshore for shellfish, and the Dockyard presided over it all as the forge for ships like Nelson's Victory. Undoubtedly, the Hartnell family were reminded of this connection almost daily.

Again, not pictured: me weighing the pros and cons of sticking my feet in a river in January

Prior to the census of 1841, it was hard to place most of the family anywhere concrete other than the church and the Dockyard where the elder Thomas worked (I say most, because of course John had to be the exception). They never appear on any of the rolls for poor relief from the church, so they must have been able to hold their own credibly enough. And like most in the area, or really the whole country, they weren't especially exceptional. The most out-of-the-norm Hartnell I could find was one of the elder Thomas' brothers who was, of all things, a clerk back in Devon. Super exciting, right?

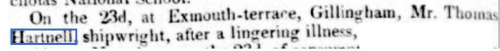

However, in 1832, just three months after Betsy's baptism, the elder Thomas Hartnell passed away. Through his death, the Hartnells appear on the map very briefly in a short account I found only a few months ago.

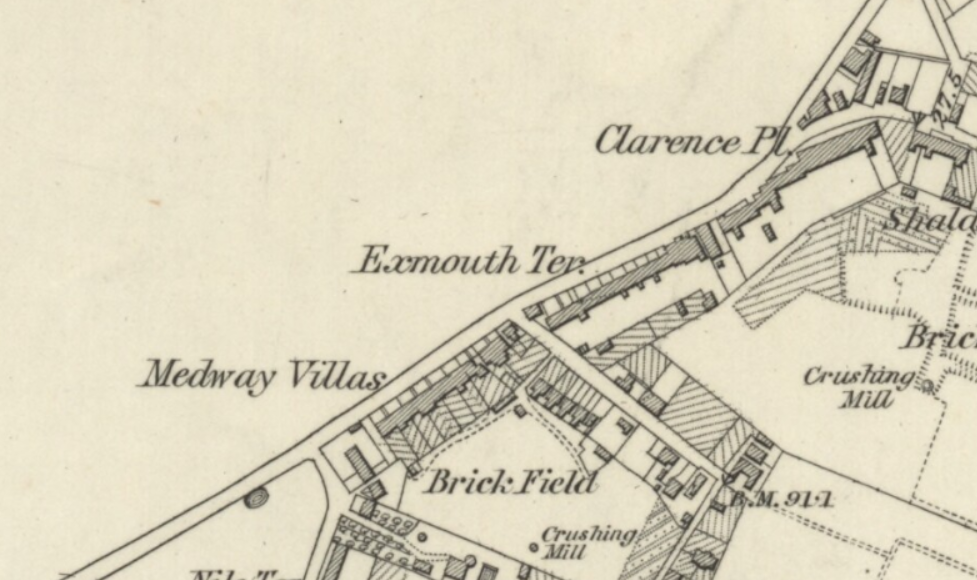

Very briefly, Thomas is mentioned in an obituary from a Maidstone newspaper dated in early May of 1832. It places him at Exmouth Terrace, now close to the location of Exmouth Road in modern Gillingham.

Church records agree with the obituary that he died on April 23rd and was buried on April 29th. As to the "lingering illness", that much is still unknown. He was 43 years old at his death, which admittedly was around the average life expectancy for most working-class men in England. But by definition, "lingering illness" could have been just about anything. John Keats, dying of tuberculosis, asked Joseph Severn to "go once and again during his lingering illness to see the place where he was to be buried". Other records of lingering illness ranged from things that sounded cancerous to ones that sounded malarial. Some clue may lie in the history of English epidemiology (is it any coincidence I'm working on this during the COVID-19 pandemic?) as between 1831 and 1833, there were massive outbreaks of Asiatic cholera and influenza. It's just as possible that Thomas Hartnell died of one of these as any other infectious disease.

What ever the cause, Thomas Hartnell's death left a widowed Sarah with five children, the oldest twelve years old and the youngest just a few months in age.

Less than a year later, Sarah and John signed an apprenticeship form on March 10th, 1833, when John was around thirteen years old. In wording, the form was extremely similar to the one signed by John's father and uncle twenty-six years prior, including the aforementioned DO NOT DO THIS list and: "[The apprentice] shall not haunt Taverns or Playhouses nor absent himself from [his job]." The apprenticeship was signed over to Yorkshireman Henry Sarge, a shoemaker on Middle Street in Brompton. On the form itself, Sarah's signature is very crisp and neat, and John's is surprisingly neat as well.

The level of John's education is unknown; as far as I can tell, none of the Hartnell siblings ever had formal schooling. However, from the contents of the Hartnell Papers at SPRI and the legibility of John and Thomas' respective signatures in Erebus' muster book, it's clear that the family had some level of education beyond the rudimentary. At the time, it wasn't compulsory for children to go to school. However, ragged schools and dame schools had gained popularity, with ragged schools in particular often being run by churches or charities. In the early 1830s, about 60% of Englishmen were literate, and less so for women. As Sarah appeared to be an avid churchgoer, it stands to reason that the Hartnells probably defaulted to a ragged school, as all five children were literate (and had very beautiful handwriting!).

I'm not sure how long John worked for Henry Sarge or if he served the full seven year apprenticeship as stated on his form from 1833. He's absent from most formal record until the census, although there may be one exception that I'll touch on in a moment.

As for Thomas Hartnell, his life was about to get much more exciting.

Thomas may or may not have had a bit more luxury of choice as to his future career. The Hartnells had been almost exclusively shipwrights at least three generations back, and a few relatives had ties to the Navy. The shadow of the Chatham Dockyard fell long over the Hartnell family, let alone the rest of Gillingham, and on April 14th, 1837, a fifteen-year-old Thomas Hartnell stepped into the boundaries of the Dockyard and signed onto the HMS Brune.

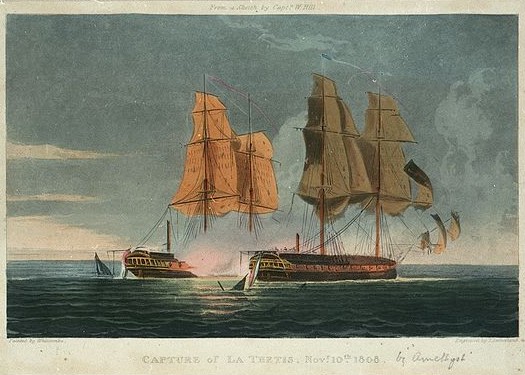

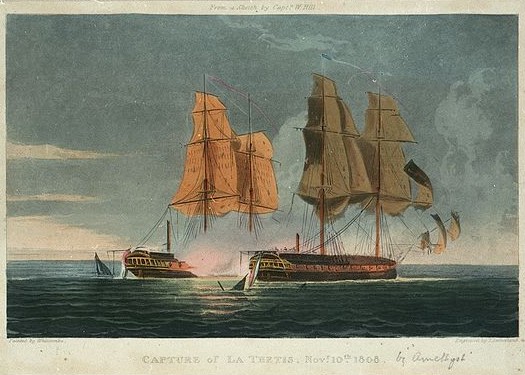

The Brune was, at the time, a learning vessel docked at Chatham. It was a far cry from the Brune's former glory as the Thétis, a 40-gun Nymphe-class frigate of the French Navy. On November 10th, 1808, Thétis was captured by the HMS Amethyst after a violent skirmish. It was refitted as a troop ship, then a victualing depot, before finally making its permanent home in Chatham.

At the time of Thomas' assignment, the Brune was under the command of Trafalgar veteran and Captain-Superintendent of the Chatham Dockyard, Captain John Clavell. It's not hard to imagine the kind of awe a teenager like Thomas might have felt as he learned and worked under Clavell's auspices. However he performed, Thomas did well enough to sign off on the Brune on December 23rd and went on to the HMS Volage a day later. About a year later, the Brune was sold and broken up.

The Volage figured heavily into the stories of both John and Thomas Hartnell, as it did for several other Franklin Expedition members. A Sixth-rate 28-gun frigate built in Portsmouth in 1825, the Volage saw action from Brazil to Turkey, and practically promised action to a teenage Thomas. Indeed, the next three years brimmed with it.

Under Captain Henry Smith, the Volage was the lead ship during the Aden Expedition. Without diving too deep into British colonization practices of the era (oh boy), the intent of the Aden Expedition was to capture the Port of Aden in what is now Yemen. Aden sat on a desirable route at the joining of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. It piqued British interests during the Napoleonic Wars, then fully flared to a straight-up need as Great Britain began to conceive of a shortcut through Suez in order to easily reach India. Unfortunately for Britain, the Sultanate of Lahej wasn't thrilled with the idea of ceding the port in its entirety. The two forces scrabbled and fought before Britain finally pulled out some stops in January of 1839.

Four ships—HMS Volage, HMS Cruizer, HCS Coote, and HCS Mahi—accompanied around 700 infantrymen on land (under the mercantile-minded East India Company, so, y'know) to launch an offense on Sira Fortress near Aden. Future Erebus lieutenant Graham Gore and Erebus AB John Strickland also served on the Volage during this engagement, watching as British forces whittled down resistance before finally capturing the port entirely. Those interested can read Captain Smith's report on the battle here.

Later that year and not to be outdone in its own colonial efforts, Volage sailed on to China in the summer of 1839 as part of the First Opium War.

Admiral Sir Charles Elliot, Chief Superintendent overseeing British trade interests in China (and future administrator of Hong Kong), had ordered Volage and 18-gun sloop HMS Hyacinth to blockade waters near the Chuenpi battery near modern-day Canton/Guangzhou, preventing British ships from entering the Humen Strait. What followed on November 3rd, 1839 was something of a chaotic mess, and somewhat feels like the equivalent of Elliot punching himself in the face. The British ship Royal Saxon entered the strait, Captain Smith fired a warning shot, Chinese junks sailed out to defend the Royal Saxon, some miscommunication happened, and the gloves promptly flew off.

Volage and Hyacinth took minimal damage and only one man was wounded on the British side, whereas the Chinese took a hit to the tune of fifteen deaths and four junks lost. As far as battles went, in appearance it didn't seem to be much more than a squabble. However, it was entirely representative of the tense state at the beginning of the war. (Also, this is a fantastic read on the Chinese version of events of the Opium Wars!)

The Volage remained in China as British forces captured Chusan the first time, before returning to England in 1841. As for Thomas Hartnell, he signed off on May 20th and went on to join the HMS Tortoise four days later.

The Tortoise's story is interesting and worth following, but we have to deviate here to hop back to Gillingham for a moment.

On June 6th, 1841, the English census was taken. Each home was given a form to fill out containing the names of everyone present at a house on the night of the 6th; the forms would be collected on the 7th by the district enumerator. Military personnel and those on ships could be included in the form, so the Hartnells recorded Thomas as among their family number. As for the ages, census takers were ordered to write exact ages for children under fifteen; anyone over fifteen would have their age rounded to the nearest whole number to the nearest multiple of five. The 49-year-old Sarah was now 45 (that was nice of the census-taker!), and the elder brothers Hartnell were both 20. Mary Ann, Charles, and Betsy all have their ages accurately recorded, and a boarder, Edward Eldrige, was included as well.

Two things to note! The first is the 'place' category, referring to 'Nelson St or East Row'. Going through the entirety of the Gillingham 'District 9' census, families are sorted into loosely-bound neighborhoods such as Wellington Place, Park Place, Lower Lines, Townsends Redoubt, Field Work Terrace, and Princes Street—all tend to be congregated around what might be considered the center of modern Gillingham.

Names have changed aplenty, but it seems like the Hartnells never moved very far away from Exmouth Terrace, which was considered part of the 'East Row' neighborhood. At the very least, we get a good idea of where they lived, and judging on how most Gillingham residents lived at the time, they probably resided in one of the rows of cottages near the Dockyard.

Next time, it's back to the Dockyard with us! Because things are about to get weird!

The level of John's education is unknown; as far as I can tell, none of the Hartnell siblings ever had formal schooling. However, from the contents of the Hartnell Papers at SPRI and the legibility of John and Thomas' respective signatures in Erebus' muster book, it's clear that the family had some level of education beyond the rudimentary. At the time, it wasn't compulsory for children to go to school. However, ragged schools and dame schools had gained popularity, with ragged schools in particular often being run by churches or charities. In the early 1830s, about 60% of Englishmen were literate, and less so for women. As Sarah appeared to be an avid churchgoer, it stands to reason that the Hartnells probably defaulted to a ragged school, as all five children were literate (and had very beautiful handwriting!).

I'm not sure how long John worked for Henry Sarge or if he served the full seven year apprenticeship as stated on his form from 1833. He's absent from most formal record until the census, although there may be one exception that I'll touch on in a moment.

As for Thomas Hartnell, his life was about to get much more exciting.

Party time.

Thomas may or may not have had a bit more luxury of choice as to his future career. The Hartnells had been almost exclusively shipwrights at least three generations back, and a few relatives had ties to the Navy. The shadow of the Chatham Dockyard fell long over the Hartnell family, let alone the rest of Gillingham, and on April 14th, 1837, a fifteen-year-old Thomas Hartnell stepped into the boundaries of the Dockyard and signed onto the HMS Brune.

The Brune was, at the time, a learning vessel docked at Chatham. It was a far cry from the Brune's former glory as the Thétis, a 40-gun Nymphe-class frigate of the French Navy. On November 10th, 1808, Thétis was captured by the HMS Amethyst after a violent skirmish. It was refitted as a troop ship, then a victualing depot, before finally making its permanent home in Chatham.

A reminder of Napoleonic-era violence and the perfect place to put a fifteen-year-old!

At the time of Thomas' assignment, the Brune was under the command of Trafalgar veteran and Captain-Superintendent of the Chatham Dockyard, Captain John Clavell. It's not hard to imagine the kind of awe a teenager like Thomas might have felt as he learned and worked under Clavell's auspices. However he performed, Thomas did well enough to sign off on the Brune on December 23rd and went on to the HMS Volage a day later. About a year later, the Brune was sold and broken up.

The Volage figured heavily into the stories of both John and Thomas Hartnell, as it did for several other Franklin Expedition members. A Sixth-rate 28-gun frigate built in Portsmouth in 1825, the Volage saw action from Brazil to Turkey, and practically promised action to a teenage Thomas. Indeed, the next three years brimmed with it.

'Splosive!

Under Captain Henry Smith, the Volage was the lead ship during the Aden Expedition. Without diving too deep into British colonization practices of the era (oh boy), the intent of the Aden Expedition was to capture the Port of Aden in what is now Yemen. Aden sat on a desirable route at the joining of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. It piqued British interests during the Napoleonic Wars, then fully flared to a straight-up need as Great Britain began to conceive of a shortcut through Suez in order to easily reach India. Unfortunately for Britain, the Sultanate of Lahej wasn't thrilled with the idea of ceding the port in its entirety. The two forces scrabbled and fought before Britain finally pulled out some stops in January of 1839.

Four ships—HMS Volage, HMS Cruizer, HCS Coote, and HCS Mahi—accompanied around 700 infantrymen on land (under the mercantile-minded East India Company, so, y'know) to launch an offense on Sira Fortress near Aden. Future Erebus lieutenant Graham Gore and Erebus AB John Strickland also served on the Volage during this engagement, watching as British forces whittled down resistance before finally capturing the port entirely. Those interested can read Captain Smith's report on the battle here.

Later that year and not to be outdone in its own colonial efforts, Volage sailed on to China in the summer of 1839 as part of the First Opium War.

Obviously, it went really well.

Admiral Sir Charles Elliot, Chief Superintendent overseeing British trade interests in China (and future administrator of Hong Kong), had ordered Volage and 18-gun sloop HMS Hyacinth to blockade waters near the Chuenpi battery near modern-day Canton/Guangzhou, preventing British ships from entering the Humen Strait. What followed on November 3rd, 1839 was something of a chaotic mess, and somewhat feels like the equivalent of Elliot punching himself in the face. The British ship Royal Saxon entered the strait, Captain Smith fired a warning shot, Chinese junks sailed out to defend the Royal Saxon, some miscommunication happened, and the gloves promptly flew off.

Volage and Hyacinth took minimal damage and only one man was wounded on the British side, whereas the Chinese took a hit to the tune of fifteen deaths and four junks lost. As far as battles went, in appearance it didn't seem to be much more than a squabble. However, it was entirely representative of the tense state at the beginning of the war. (Also, this is a fantastic read on the Chinese version of events of the Opium Wars!)

The Volage remained in China as British forces captured Chusan the first time, before returning to England in 1841. As for Thomas Hartnell, he signed off on May 20th and went on to join the HMS Tortoise four days later.

The Tortoise's story is interesting and worth following, but we have to deviate here to hop back to Gillingham for a moment.

And all genealogists rejoiced!

On June 6th, 1841, the English census was taken. Each home was given a form to fill out containing the names of everyone present at a house on the night of the 6th; the forms would be collected on the 7th by the district enumerator. Military personnel and those on ships could be included in the form, so the Hartnells recorded Thomas as among their family number. As for the ages, census takers were ordered to write exact ages for children under fifteen; anyone over fifteen would have their age rounded to the nearest whole number to the nearest multiple of five. The 49-year-old Sarah was now 45 (that was nice of the census-taker!), and the elder brothers Hartnell were both 20. Mary Ann, Charles, and Betsy all have their ages accurately recorded, and a boarder, Edward Eldrige, was included as well.

Two things to note! The first is the 'place' category, referring to 'Nelson St or East Row'. Going through the entirety of the Gillingham 'District 9' census, families are sorted into loosely-bound neighborhoods such as Wellington Place, Park Place, Lower Lines, Townsends Redoubt, Field Work Terrace, and Princes Street—all tend to be congregated around what might be considered the center of modern Gillingham.

Here-ish! Vaguely in this direction!

Names have changed aplenty, but it seems like the Hartnells never moved very far away from Exmouth Terrace, which was considered part of the 'East Row' neighborhood. At the very least, we get a good idea of where they lived, and judging on how most Gillingham residents lived at the time, they probably resided in one of the rows of cottages near the Dockyard.

Next time, it's back to the Dockyard with us! Because things are about to get weird!

Comments

Post a Comment