hide and seek with a ghost; the non-fictional biography of john hartnell, and the fiction to come

Creating a fictional character is something of a mad science. You feel a little bit like Victor Frankenstein at times, looking down at your patchwork creation that is a little bit of one thing you've seen, a little bit of another. You see some of your friends in this character, some of your enemies, something you saw on TV or read in a book. Your character becomes what you want it to be, and sometimes what you don't. But in the end, this character is yours. You can do what you'd like with them to a degree.

Writing about an actual person might just be a lesson in futility, in comparison. I sometimes wonder if it's easier for some people than others, writing out detailed biographies and combing through letters and records in musty libraries and archives. In this case, there's some line to follow that's been set out long before you even began your work. There's a timeline, although not always definitive, and there's major events throughout the timeline that you can use as waypoints. So-and-so was at the Battle of Something-or-another in anno domini 9999. There's a waypoint. If you go back in time to this place at this time, there you'll find your subject.

But this is where I wonder.

I wonder what that subject was doing at that exact moment. If you, as a writer, were not at this event (or even born anywhere near it), how do you know what that person was doing? Aside from maybe some diary entries and witness accounts, how can you say for sure what their actions or thoughts were? And that's in the fortunate case that the subject you've selected actually has several accounts written about them or by them. In other cases, how do you fill in blanks in the timeline that can stretch on for years, if not decades?

More than that, I marvel at how a biography can be written and not seem rigid with facts. Yes, so-and-so was born on this date in this place, and they went to this location, on and on. In writing a fictional character, you have the freedom to say that a character went to a location and felt the empty sense of melancholy often associated with the wide open gray yawning of the sea. You can provide an endless running commentary on thoughts and feelings, because there's nothing stopping you from saying so. In the case of a real person, especially one that lived in an era far removed from your own, the creative process has to fill in all those blanks.

I've found this in the case of two of my subjects, able-bodied seamen John and Thomas Hartnell; two brothers who, in 1845, embarked on the infamous Franklin Expedition to map out the last section of the Northwest Passage. Those familiar with the expedition itself can recognize John Hartnell at a hundred paces. His face christened at least one edition of Frozen in Time, an account by Owen Beattie and John Geiger about the exhumation of three of the expedition's arguably more fortunate members.

Petty Officer John Torrington might be more famous as far as immediate recognition and legacy. Margaret Atwood poetically wondered after his last moments in her short story The Age of Lead. Sheenagh Pugh marveled at Dr. Beattie's fortune of holding John Torrington's frail body in her poem Envying Owen Beattie. Even Iron Maiden sang (rocked?) from Torrington's perspective in Stranger in a Strange Land. He's had plenty of short stories, poems, and songs written about and for him, despite having relatively few contemporary documents actually giving a precise stance and view of his life and family. There is no completely rigid biography about John Torrington, and in cases of James Taylor's Frozen Man, John Torrington is only present as the inspiration, but not even present in name. His image, striking as it is sad, has stirred many imaginations.

I have to divert for just a moment to say that I owe John Torrington for two things, even though I'm not writing about him specifically. The first is for an almost hilarious childhood trauma on par with the fear of clowns and of the dark. When I was about five or six years old, a family member bought me a book called Mummies & Their Mysteries by Charlotte Wilcox. My disclaimer on this book is that no, theoretically, it's not a book meant for easily freaked out kids. It was however, great for a kid like me who got hauled from one end of the country to the other, looking at Civil War battlefields and mummies in museums. I loved the pictures of the Lindow Man and King Tutankhamun. I would page through the book for hours on end, marveling at Peruvian mummies and bog bodies alike.

Until I got to John Torrington.

I always knew which page he was on, and even in my attempts to skip it, it would always end up falling open, which would result in me essentially having to be peeled off the ceiling in fear. He terrified me. The color image of him taking up a full page was enough to get me to snap the book shut. His image kept me awake for hours at night, because I was so sure that the shambling frozen ghost of John Torrington was going to barge into my room and... I don't know. He was going to do something awful, and six year old me decided this was an absolute certainty.

Hilarious in retrospect, but back then, he was a legitimate boogeyman to me. Fast forward about eighteen years, and now I owe him for both my petrifying fear and for a very invested interest. Remembering that book is what got me looking at the Franklin Expedition mummies again. For a few moments, I remembered my fear and cringed a little at his image. Then, I realized I was now looking back at someone who had been younger than me when he died, and died in an utterly miserable way that I wouldn't wish on anyone.

At twenty-four years old by this point, my eyes moved over to John Hartnell, Torrington's comrade-in-ice. There was something even more striking about him, made even more poignant at our shared age. The first time I actually made an effort to read and research him, I was a few months away from my twenty-fifth birthday. He was in the Arctic by his, and I was researching him in London by mine.

Without immediately using an image of his body, I'll take a moment to describe him by the first image I saw of him. It was a photograph taken after his watchcap and outer shirt were removed. The first thing I registered about him was his hair, appearing pitch-black, parted from left to right in a style that seemed oddly modern to me. Three separated locks were plastered to his forehead even before the scientists removed his hat. His right eye appeared caved-in or sunken, and his left looked tired. Two small freckles edged his left eye on the outside. His nose must have been a distinguishing feature in life, wide and rounded. His teeth were in two even rows (I'd find out later that his mandibular first molars were impacted, but you couldn't see that in the photograph), his dehydrated lips peeled back in something that has been described as a grimace or a grin. I found it more like playing with your lips in a mirror, tugging them back to see all of your teeth at once. The barest fringes of a dark beard were on his chin, although the lighting gave him the illusion of almost being clean shaven.

The strange thing about this image is that while my logical mind immediately registered that he was dead, my imagination took off at a speed that my frontal lobe couldn't reel in. His sunken eye, dehydrated eyelids and lips, and odd coloration didn't seem to matter. I felt like, for just a moment, I could see him alive.

Working in archaeology sometimes means that I have to rewind the great earthly clock and put things in their logical places. In my head, I have to resurrect people long dead and place them like actors in a film. John Hartnell was suddenly walking along coalsmoke-stained piers and docks. He was climbing up to a crow's nest. He was at the helm of a ship. He was on the ice, gazing out at a desolate, forbidding monochrome landscape. He was in the ice, only just dead and not yet completely gone.

I knew within days that I needed to write about him.

The thing is, John Hartnell, aged 25 years old from the Chatham area of Kent, son of Thomas and Sarah Hartnell, was nearly impossible to find. His solid biographical timeline was tempestuous at best and utterly invisible at worst. The fact of the matter was that he was, for all intents and purposes, an average sailor who was not particularly remarkable prior to his last journey and death. Notwithstanding his striking appearance, he probably would have blended in with the crowds of Chatham with ease. On a roll of residents, his name would not have stuck out as unusual. In history, he seems to be the footnote of a footnote.

I had some good fortune in that several people went ahead and put the proverbial nose to the grindstone in order to find some details about the lives of him and his family. Internet detective work has been able to fill in a few blanks, and I'd be remiss to not mention some of the best.

Jaeschylus has been the ultimate boon to any research I needed to do. Her amazing blog, Stars Over Ice has been a go-to for finding the first strings of any part of John's life that I wanted to follow. Ralph Lloyd-Jones' article The men who sailed with Franklin features another interesting and engaging view of John and his younger brother, Thomas. The records of the St. Mary Magdalene church in Gillingham and the dedicated people who work with this church and with the maintenance of its cemetery have also been an enormous help.

With a few of these wonderful resources now in my arsenal (bless 'em), I was able to build something of a timeline of halfway decent solidity in order to follow John Hartnell's life from beginning to end and beyond. The patches in between were going to have to receive the masonry of creative writing to fill them in.

To start, I managed to find the written record of John Hartnell's baptism, but not his birth. Further research alerted me that at the time, lower income families sometimes waited until baptism to have a child recorded in any official documents, partially because of the high infant mortality rate. It seems that around 1820, when John was born, the average wait for this event was around a month or two. Indeed, no record of John's actual birthdate seems to exist (yet), but he was baptized on July 16th, 1820.

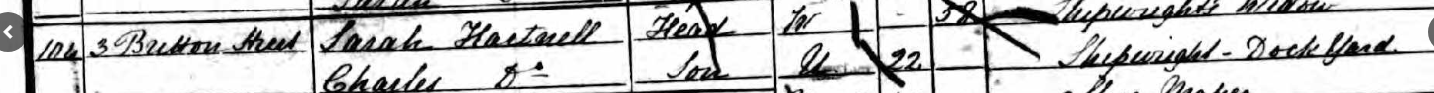

This record also shows that he was possibly born in Brompton, Kent, and his father's occupation (far right) was shipwright, presumably at the Chatham dockyards nearby. If the one month rule applies, that means that John Hartnell was probably born either in May or June of 1820. Of course, that's just an estimate, but given the context clues of the era, it's not entirely impossible.

His younger brother, Thomas, was also recorded as a baptism in the parish register at St. Magdalene's two years later.

Here, his baptism date is listed as May 12th, 1822. Interestingly, his epitaph on a tombstone that I'll mention in a bit says that he was born on March 12th, two months before his baptism. Again, from Brompton, and the elder Thomas Hartnell was still a shipwright at the time of his birth. Given clues again, it's possible that by Thomas' birth in 1822, John might have been just short of two years old.

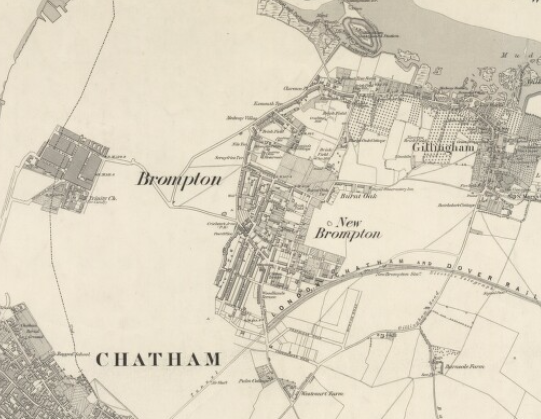

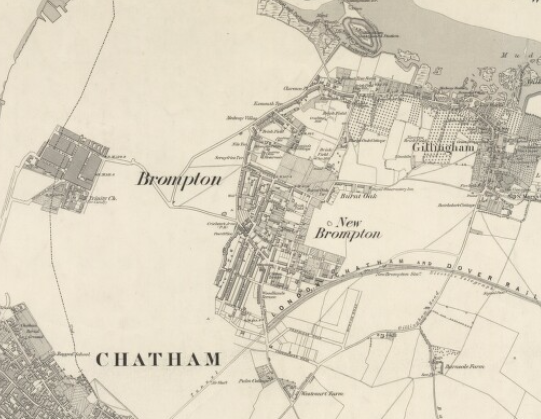

An interesting note is that, aside from John and Thomas, there were three other surviving Hartnell siblings; Mary Ann (b.1826; baptized Sept 17th), Charles (b.1828; baptized June 1st), and Betsey (b.1832; baptized Jan 22nd). Thomas and Sarah Hartnell had another son, born two years after the younger Thomas, also named Charles, baptized September 19th, 1824. According to burial records for the parish, he died at 15 months and was buried on December 11th, 1825. Two things to note on the family here is that the elder Thomas Hartnell was a shipwright from at least 1820 to 1832, judging by the records of his childrens' baptisms. Also, for John and Thomas' baptisms, the family is recorded as living in Brompton, Kent. As of the first Charles' record in 1824, they were shown to be living in New Brompton, rather than just Brompton. Whether or not that meant that the family moved some time between 1822 and 1824, or names simply changed, I'm not entirely sure yet. I have found a map of the area dating between 1863 and 1865, showing four communities that feature in the Hartnell story.

A link to the full map (and its amazing zoom qualities!) is here.

There is some confusion in the Hartnell family that occurs shortly after Betsey's birth in 1832. According to burial records for St. Mary Magdalene's, Thomas Hartnell died on April 23rd, 1832, age 43. The tombstone in question reads:

The fact came down to this; these were two young men in a mid-to-low income family. By the time they left, the muster record shows that John was twenty-five and Thomas was twenty-three. It's another guess of imagination to wonder if they were apprehensive about their joint decision. They were leaving their mother, younger brother, and two younger sisters behind, on a journey that they weren't sure they would return from. This is a moment, a waypoint, where fiction will have to fill in the gaps of fact.

Another question that comes up on that May day in 1845 was if John was yet showing signs of any illness. Evidently, even if he was, it wasn't serious enough to be sent back with several other sailors early on in the voyage. But by the evidence of his autopsy outlined in Frozen in Time, John's health had not always been the best, and recent injuries would have taken a toll.

For this, I had to fill in the gaps with a trusted forensic anthropology instructor and two medical professionals. Again, mysteries came up. The lead poisoning and zinc deficiency controversies were pushed by the wayside for a moment as we went over other details in John's very much posthumous examination. He had osteomyelitis in one foot, meaning an infection in one of his bones. My anthropology instructor suggested that it was very likely that this infection would have spread from his lungs due to the tuberculosis that he ended up succumbing to, as that is a common cause of osteomyelitis in adults. The infection itself spreads through the bloodstream, and although, on its own, the infection in his foot wouldn't have caused him an enormous amount of distress other than some pain, the symptoms on top of that which he already had would have been miserable.

He also had evidence of a compression fracture in his C6 vertebrae, its location shown here for reference.

As this link suggests, his injury might have resulted from a fall while on board, probably onto his back. An injury in his ankle might have been sustained from this possible fall as well. Regardless of what caused the injury, it would have been painful, and eventually very stiff.

The cause of his actual death, however, is far more dismal than any fall or fracture. Tuberculosis, historically, has been viewed as a death sentence. Combined with pneumonia, the possibilities of some lead interference or zinc deficiency, and other symptoms would have made death a slow and painful affair. Although he might have been able to conceal his symptoms at first, as illness on board ships was common, eventually it would have become obvious to the crew that he was too ill to continue working. He had clearly been ill enough for a period of time to cause massive weight loss, which would have been even more obvious on a person who was 5'11", a towering height for the time. It progressed enough that he may have been refusing food--of which the expedition bragged on having enough supplies to last them years--or vomiting so much that he wouldn't have been able to digest it regardless. He would have been feverish, possibly hallucinating, and eventually comatose. Death would have been a relief compared to what John Hartnell went through at the end of his life.

His shipmates appeared to care enough for him to make his last moments presentable. He was dressed from the waist up in multiple layers, including one of Thomas' shirts, and his wool watchcap. His nails may have been cleaned and his hair combed. A pillow was sewn for him, in comparison to the woodshavings that John Torrington rested on. It seemed as though John Hartnell was made to look as presentable as possible, and to appear as he would have as an active AB, dressed from the waist up as if ready for duty.

Although the name plate on his casket was taken by the Inglefield and Sutherland expedition in 1852, it was probably hand hammered as was John Torrington's and William Braine's. As many have postulated, Sir John Franklin, an incredibly religious man, would have taken the chance to hold a funeral for John Hartnell. While not the first sailor to die on the expedition, he was the first of the crew of the Erebus to die. As that was Franklin's ship, that may have carried extra meaning for the captain.

There seems to be a debate as to who performed the infamous inverted autopsy of John Hartnell, with his bizarre upside-down Y incision. Owen Beattie and John Geiger have said that it must have been done by a doctor on the Erebus, possibly physician Henry Goodsir. Ralph Lloyd-Jones says that it was done by Inglefield and Sutherland during their 1852 exhumation that damaged Hartnell's right arm and possibly his right eye. I personally elect to agree with Beattie and Geiger on this point, as although the autopsy seems hurried, I find it much more difficult to think that the 1852 attempt would have taken the time, after hacking through layer upon layer of permafrost, to thaw out John Hartnell, completely undress him, perform the autopsy (mind you, they would have to spend the time to thaw him out down to the organs they clearly removed), sew him back up, redress him, and bury him again, all while fighting the elements using only the protections afforded in 1852. Judging by the condition of his body and clothing when Dr. Beattie's team exhumed him, Inglefield and Sutherland may have taken only the time to dig down to the casket, open it, thaw John out enough to see him and pull his right arm out of the ice, examine his face, and make some hurried deductions based on what they could see and feel. It's still entirely conjecture until more evidence comes up or any further records from 1846 or 1852, but I've at least picked the story I'd like to go with.

The solidity of the facts behind John Hartnell's last days are nothing that is based on record aside from that which was in his autopsy in the 1980s. So much of it is fueled on imagination and prior knowledge of similar cases. To take a step even further away from what can be considered solid fact is to think of what Thomas Hartnell, John's younger brother, went through.

As of now, in 2017, Thomas Hartnell's body has never been found. Although the Erebus and Terror have been discovered to great fanfare and excitement, their crews are still shrouded in mist, so to speak. It's unclear when Thomas died, or how he died, or even where he died. We can't be sure of what his feelings were at his older brother's death, or how he felt about his brother prior. He apparently felt strongly enough about him to give him his shirt, made of a more expensive woven striped fabric, as seen in this photograph.

Based on tradition, Thomas may have been expected to help in funeral preparations, to say some words at the funeral itself, and possibly to put the first shovelful of gravel on his brother's grave. Hundreds of possibilities for thoughts may have gone through his head. He was now the oldest of his siblings, the one responsible for them when (and if) he returned. It may have been a very emotional time for him, having grown up beside John and now knowing he would never see him again. Once again, it's impossible to know how he felt, and how he continued to feel from that moment on Beechey Island to the very end of his life, whenever that occurred.

When it became clear in England that the Franklin Expedition was lost, it's another matter of imagination entirely to know how the Hartnell family felt. Judging by tales from Donald Bray and Brian Spenceley, two descendants of the Hartnells, stories were passed down the line of two brothers who went into the Arctic and didn't return. The family received Thomas' Arctic service medal and his pay, but did not receive John's on account of the crown debt. It wasn't received until January 4th, 1986--one hundred and forty years to the day--to Donald Bray.

While this may seem like a large amount of John's life is recorded (it took me nearly four hours to write this entry), in reality, it's almost nothing. We have his baptism records and that of his siblings, some census records that give us a time and place of residence as well as his career, two muster records from two different ships, evidence of a debt but no evidence of its cause, and the clear and plentiful evidence of his death. His muster records from the Volage say he was 5'11"1/2, with black hair, hazel eyes, and a sallow complexion. His younger brother was fair in appearance, a few inches shorter, freckled, and tattooed on one arm. From what's known, John Hartnell never married and never had children of his own. There's no letters known yet (to me, anyway) of any friends, relationships beyond his family, or anything beyond a very small circle of people. Records and letters may be out there, or they may have very well been lost in the tide, in comparison to documentation of people of greater note than an AB from a small town in Kent.

It's this lack of information that I suppose I found most enticing when I decided to write about John and Thomas. In a life that seems scanty on real hard evidence, there are situations that would have been so ripe with emotion and feeling that as a writer and a historian, it just seems natural to try to explore.

For every time I've tried to discover something more about the brothers and the Hartnell family, more questions come up. It really has been like hide and seek, or like a treasure map with whole sections cut out or faded away. My end goal is this; I want to write a story about this family and these two men in particular that stays as close to the facts as it can, and does so as respectfully and honestly as possible, while still filling in those blanks that I find so enticing. I want John Hartnell's life to become vibrant and real again, to have at least some of the attention paid to John Torrington. And I want to highlight the life of someone comparatively average, like a seaman. Thousands of pages have been paid to people like Franklin, Crozier, Fitzjames, and more. For someone whose occupation was vital to the expedition as well, I feel like it would be a fitting tribute not only to him, not only to the expedition, but to thousands more like John Hartnell, who were in lower positions of ranking, but who lived and died in their line of work. I don't want people like him to be forgotten, or only known for purely macabre reasons (although I do realize the hypocrisy in wanting to write about him due to a picture from his exhumation). If anything, I want to resurrect him, just for a moment, and give him a chance to speak.

Writing about an actual person might just be a lesson in futility, in comparison. I sometimes wonder if it's easier for some people than others, writing out detailed biographies and combing through letters and records in musty libraries and archives. In this case, there's some line to follow that's been set out long before you even began your work. There's a timeline, although not always definitive, and there's major events throughout the timeline that you can use as waypoints. So-and-so was at the Battle of Something-or-another in anno domini 9999. There's a waypoint. If you go back in time to this place at this time, there you'll find your subject.

But this is where I wonder.

I wonder what that subject was doing at that exact moment. If you, as a writer, were not at this event (or even born anywhere near it), how do you know what that person was doing? Aside from maybe some diary entries and witness accounts, how can you say for sure what their actions or thoughts were? And that's in the fortunate case that the subject you've selected actually has several accounts written about them or by them. In other cases, how do you fill in blanks in the timeline that can stretch on for years, if not decades?

More than that, I marvel at how a biography can be written and not seem rigid with facts. Yes, so-and-so was born on this date in this place, and they went to this location, on and on. In writing a fictional character, you have the freedom to say that a character went to a location and felt the empty sense of melancholy often associated with the wide open gray yawning of the sea. You can provide an endless running commentary on thoughts and feelings, because there's nothing stopping you from saying so. In the case of a real person, especially one that lived in an era far removed from your own, the creative process has to fill in all those blanks.

I've found this in the case of two of my subjects, able-bodied seamen John and Thomas Hartnell; two brothers who, in 1845, embarked on the infamous Franklin Expedition to map out the last section of the Northwest Passage. Those familiar with the expedition itself can recognize John Hartnell at a hundred paces. His face christened at least one edition of Frozen in Time, an account by Owen Beattie and John Geiger about the exhumation of three of the expedition's arguably more fortunate members.

Petty Officer John Torrington might be more famous as far as immediate recognition and legacy. Margaret Atwood poetically wondered after his last moments in her short story The Age of Lead. Sheenagh Pugh marveled at Dr. Beattie's fortune of holding John Torrington's frail body in her poem Envying Owen Beattie. Even Iron Maiden sang (rocked?) from Torrington's perspective in Stranger in a Strange Land. He's had plenty of short stories, poems, and songs written about and for him, despite having relatively few contemporary documents actually giving a precise stance and view of his life and family. There is no completely rigid biography about John Torrington, and in cases of James Taylor's Frozen Man, John Torrington is only present as the inspiration, but not even present in name. His image, striking as it is sad, has stirred many imaginations.

I have to divert for just a moment to say that I owe John Torrington for two things, even though I'm not writing about him specifically. The first is for an almost hilarious childhood trauma on par with the fear of clowns and of the dark. When I was about five or six years old, a family member bought me a book called Mummies & Their Mysteries by Charlotte Wilcox. My disclaimer on this book is that no, theoretically, it's not a book meant for easily freaked out kids. It was however, great for a kid like me who got hauled from one end of the country to the other, looking at Civil War battlefields and mummies in museums. I loved the pictures of the Lindow Man and King Tutankhamun. I would page through the book for hours on end, marveling at Peruvian mummies and bog bodies alike.

Until I got to John Torrington.

I always knew which page he was on, and even in my attempts to skip it, it would always end up falling open, which would result in me essentially having to be peeled off the ceiling in fear. He terrified me. The color image of him taking up a full page was enough to get me to snap the book shut. His image kept me awake for hours at night, because I was so sure that the shambling frozen ghost of John Torrington was going to barge into my room and... I don't know. He was going to do something awful, and six year old me decided this was an absolute certainty.

Hilarious in retrospect, but back then, he was a legitimate boogeyman to me. Fast forward about eighteen years, and now I owe him for both my petrifying fear and for a very invested interest. Remembering that book is what got me looking at the Franklin Expedition mummies again. For a few moments, I remembered my fear and cringed a little at his image. Then, I realized I was now looking back at someone who had been younger than me when he died, and died in an utterly miserable way that I wouldn't wish on anyone.

At twenty-four years old by this point, my eyes moved over to John Hartnell, Torrington's comrade-in-ice. There was something even more striking about him, made even more poignant at our shared age. The first time I actually made an effort to read and research him, I was a few months away from my twenty-fifth birthday. He was in the Arctic by his, and I was researching him in London by mine.

Without immediately using an image of his body, I'll take a moment to describe him by the first image I saw of him. It was a photograph taken after his watchcap and outer shirt were removed. The first thing I registered about him was his hair, appearing pitch-black, parted from left to right in a style that seemed oddly modern to me. Three separated locks were plastered to his forehead even before the scientists removed his hat. His right eye appeared caved-in or sunken, and his left looked tired. Two small freckles edged his left eye on the outside. His nose must have been a distinguishing feature in life, wide and rounded. His teeth were in two even rows (I'd find out later that his mandibular first molars were impacted, but you couldn't see that in the photograph), his dehydrated lips peeled back in something that has been described as a grimace or a grin. I found it more like playing with your lips in a mirror, tugging them back to see all of your teeth at once. The barest fringes of a dark beard were on his chin, although the lighting gave him the illusion of almost being clean shaven.

The strange thing about this image is that while my logical mind immediately registered that he was dead, my imagination took off at a speed that my frontal lobe couldn't reel in. His sunken eye, dehydrated eyelids and lips, and odd coloration didn't seem to matter. I felt like, for just a moment, I could see him alive.

Working in archaeology sometimes means that I have to rewind the great earthly clock and put things in their logical places. In my head, I have to resurrect people long dead and place them like actors in a film. John Hartnell was suddenly walking along coalsmoke-stained piers and docks. He was climbing up to a crow's nest. He was at the helm of a ship. He was on the ice, gazing out at a desolate, forbidding monochrome landscape. He was in the ice, only just dead and not yet completely gone.

I knew within days that I needed to write about him.

The thing is, John Hartnell, aged 25 years old from the Chatham area of Kent, son of Thomas and Sarah Hartnell, was nearly impossible to find. His solid biographical timeline was tempestuous at best and utterly invisible at worst. The fact of the matter was that he was, for all intents and purposes, an average sailor who was not particularly remarkable prior to his last journey and death. Notwithstanding his striking appearance, he probably would have blended in with the crowds of Chatham with ease. On a roll of residents, his name would not have stuck out as unusual. In history, he seems to be the footnote of a footnote.

I had some good fortune in that several people went ahead and put the proverbial nose to the grindstone in order to find some details about the lives of him and his family. Internet detective work has been able to fill in a few blanks, and I'd be remiss to not mention some of the best.

Jaeschylus has been the ultimate boon to any research I needed to do. Her amazing blog, Stars Over Ice has been a go-to for finding the first strings of any part of John's life that I wanted to follow. Ralph Lloyd-Jones' article The men who sailed with Franklin features another interesting and engaging view of John and his younger brother, Thomas. The records of the St. Mary Magdalene church in Gillingham and the dedicated people who work with this church and with the maintenance of its cemetery have also been an enormous help.

With a few of these wonderful resources now in my arsenal (bless 'em), I was able to build something of a timeline of halfway decent solidity in order to follow John Hartnell's life from beginning to end and beyond. The patches in between were going to have to receive the masonry of creative writing to fill them in.

To start, I managed to find the written record of John Hartnell's baptism, but not his birth. Further research alerted me that at the time, lower income families sometimes waited until baptism to have a child recorded in any official documents, partially because of the high infant mortality rate. It seems that around 1820, when John was born, the average wait for this event was around a month or two. Indeed, no record of John's actual birthdate seems to exist (yet), but he was baptized on July 16th, 1820.

This record also shows that he was possibly born in Brompton, Kent, and his father's occupation (far right) was shipwright, presumably at the Chatham dockyards nearby. If the one month rule applies, that means that John Hartnell was probably born either in May or June of 1820. Of course, that's just an estimate, but given the context clues of the era, it's not entirely impossible.

His younger brother, Thomas, was also recorded as a baptism in the parish register at St. Magdalene's two years later.

Here, his baptism date is listed as May 12th, 1822. Interestingly, his epitaph on a tombstone that I'll mention in a bit says that he was born on March 12th, two months before his baptism. Again, from Brompton, and the elder Thomas Hartnell was still a shipwright at the time of his birth. Given clues again, it's possible that by Thomas' birth in 1822, John might have been just short of two years old.

An interesting note is that, aside from John and Thomas, there were three other surviving Hartnell siblings; Mary Ann (b.1826; baptized Sept 17th), Charles (b.1828; baptized June 1st), and Betsey (b.1832; baptized Jan 22nd). Thomas and Sarah Hartnell had another son, born two years after the younger Thomas, also named Charles, baptized September 19th, 1824. According to burial records for the parish, he died at 15 months and was buried on December 11th, 1825. Two things to note on the family here is that the elder Thomas Hartnell was a shipwright from at least 1820 to 1832, judging by the records of his childrens' baptisms. Also, for John and Thomas' baptisms, the family is recorded as living in Brompton, Kent. As of the first Charles' record in 1824, they were shown to be living in New Brompton, rather than just Brompton. Whether or not that meant that the family moved some time between 1822 and 1824, or names simply changed, I'm not entirely sure yet. I have found a map of the area dating between 1863 and 1865, showing four communities that feature in the Hartnell story.

A link to the full map (and its amazing zoom qualities!) is here.

There is some confusion in the Hartnell family that occurs shortly after Betsey's birth in 1832. According to burial records for St. Mary Magdalene's, Thomas Hartnell died on April 23rd, 1832, age 43. The tombstone in question reads:

IN MEMORY OF

THOMAS HARTNELL

LATE SHIPWRIGHT IN H. M. YARD

CHATHAM

WHO DIED APRIL 23rd 1832 AGED 43 YEARS

AND OF SARAH HIS WIFE

WHO DIED MARCH 30th 1854 AGED 61 YEARS

"It is better to trust in the Lord than to

put confidence in Man"

There is certainly no confusion about this headstone and to whom it belongs, as just after this shared epitaph is written:

ALSO TO JOHN SON OF THE ABOVE

WHO DIED IN THE EXECUTION OF HIS DUTY

AS SEAMAN ON BOARD H. M. SHIP EREBUS

IN THE ILL FATED EXPEDITION UNDER

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN

HIS REMAINS LIE BURIED ON BEECHEY ISLAND

IN THE ARCTIC SEAS

WHERE HIS SURVIVING SHIPMATES

PLACED THE FOLLOWING INSCRIPTION

"DIED JANY. 4Th 1846

JOHN HARTNELL, A. B.

H. M. SHIP EREBUS AGED 26 YEARS"

"Thus saith the Lord of Hosts, consider your ways"

ALSO THOMAS BROTHER OF THE

ABOVE AND LIKEWISE ONE OF THE CREW

OF THE UNFORTUNATE EREBUS WHOSE FATE

NO DISCOVERY HAS YET BEEN MADE

HE WAS BORN MARCH 12th 1823

While this might on its own not seem remarkable aside from giving dates and ages at death of John and Thomas' parents, it provides a short confusing window as to the elder Thomas Hartnell. The aforementioned amazingly wonderful Jaeschylus directed me to An Old Man-of-war's-man's Yarn by Richard Heathcote Gooch. In it, the author recounts meeting with a man that is depicted as being the father of John and Thomas, now an old man long after the deaths of his sons. If this is a true account, it raises a few questions about the man in the story, as Thomas Hartnell was dead for over a decade by the time John and Thomas left for the Arctic. Even more peculiar on that front is the 1841 census.

There are a few things to note on this particular census. The first is the misspelling of Hartnell as Heartnell on the first page. It's spelled correctly on the immediate second page, which may have simply meant that the census-taker just wrote what he had heard, among other possibilities. Sarah is listed as 45 years old (I originally mistook this as '65'!). John is listed as being twenty years old and his occupation is a shoemaker (written as Shoe M. as a common abbreviation). Thomas is also listed as being twenty years old, despite the two year age difference, and is employed as a seaman. Mary Ann is 15, Charles is 13, and Betsey is 9. Of the immediate family, only John and Thomas are employed. However, another unrelated member of the household is listed as Edward Eldrige, also aged 45. He's listed as a ropemaker and was not born in the same county as the Hartnell family, meaning he's not originally from Kent. Further prodding shows that Edward is not married and has no children of his own, which leaves a puzzling mystery as to who he was and what he was doing at the Hartnell house. It's very likely that he was boarding with them possibly as a means of income to the family, as there's no listing of Sarah ever getting remarried.

The Hartnells are also listed as living on either Nelson Street or East Row. Looking through the rest of this record shows that these two locations seemed to be a general neighborhood that many families were listed in. Oddly enough, the modern Nelson Street is not where the original one was (complete with fancy new housing), and the closest East Row was in Chatham rather than Brompton. It also seems as though many families freely cycled between saying they were from Brompton, Gillingham, or Chatham, possibly in the same way suburban people will often say that they're from the largest city close to them rather than their actual city. It might definitely be worth some further research to see exactly where the Hartnells lived.

A later census taken when Charles was 22 and Sarah 58 shows that the family has been reduced and has moved.

Sarah and Charles now live on Breckon Street, with Sarah listed as a shipwright's widow and Charles as a shipwright at the Chatham dockyard. By this point, John and Thomas are both presumed dead, and it's very likely that Mary Ann and Betsey are both married, although their records fade into obscurity until I find something else about them.

Rewinding back to the 1841 census, it's interesting to note John Hartnell's occupation as shoemaker. Going through Kent records of advertisements and directories (here is a particularly great example from 1838), John must not have owned his own shop or practice; at least, not in Chatham. He may have been an apprentice or worked under someone else for the time. But two interesting things come up on this point.

The first is that, obviously, he does not continue his trade of shoemaker much longer after the 1841 census is taken. In fact, it's very likely that he did not even finish out 1841 in his original trade. Thomas, two years younger, is a seaman at that point, and soon enough, John will be as well. This provides all matter of possibilities as to why John made this change. Growing up along the Medway River in Kent and near the Chatham Dockyards, John would have had ample opportunity to observe seaman and people who made their trade on ships nearly every day of his life. His father was a shipwright, his brother was a seaman, and his younger brother would one day become a shipwright as well. That's not even counting for the possibility of uncles or cousins who may have been in the industry. The Hartnells were constantly surrounded by reminders of the sea.

So why did he become a shoemaker first? Why didn't he continue that trade? Why did he become a seaman after his younger brother did?

That leads to the second interesting point, and one that has become a high mystery to me. John Hartnell had a crown debt and died with it hanging over him and his family. A crown debt is simply as it says; it is a debt to the English Crown. One of my favorite history professors who specializes in English history puzzled over this with me as well, and our results weren't exactly satisfying. A crown debt could have been nearly anything. It could have been for a loan taken out for many reasons. It could have been to pay damages on something else. And, by this point in time, the crown debt is an inherited thing. If a father dies without having paid his debt, it falls to his eldest to pay. John Hartnell might have had this debt for taking out a loan on his own (possibly for his trade?) or it could have been his father's and fell to him in 1832 after his father died. While crown debts could apply to criminal fines as well, there is, as of yet, no records I've found of John Hartnell ever having been arrested, detained, or fined for any crime. He did not appear to be press ganged into the Navy either. By all accounts, he seems to have joined the Navy on his own free will, and even seems to ghost his brother's footsteps onto different ships.

The debt was also roughly £117, equivalent to around £13,000 today. That would have been extremely difficult to pay off, especially on either a shoemaker's pay. Although it's hard to find what the wages would have been then, John might have made roughly ~15s. a week as a common worker around the age of twenty years old. Although London is not Chatham, Liza Picard gives an excellent idea of how the cost of living might have been for a family in London around 1856:

Two rooms in London: 5s

Coals for fire (less in summer): 1s 1d

Bread (6 four lb loaves): 4s 6d

Vegetables: 1s 1d

Meat: 2s 6d

Milk: 3d

Coffee, tea, and sugar: 2s 6d

Considering that by the 1841 census, only John and Thomas are working and the Hartnell family may be receiving income from another average laborer, this family is not making very much money, let alone to pay off a debt that size. Thomas, as a seaman, would have earned more, and with what was to come, he may have planted the idea in John's head.

This link provides at least some insight into the income of an AB, or able-bodied seaman leaving on the Erebus. The passage describes William Orren, aged 34, an AB on the Erebus who also hailed from Chatham.

There's no actual way of knowing what John and Thomas did with their pay, and as of this moment, I haven't been able to actually look at the muster record to see when they signed on to work on the Erebus. John had only been in the Navy four years by this point, and had been on one other ship, the HMS Volage. To know what the brothers were immediately doing with their pay would be to know their personalities, and as of now, we have no real indicator for what they were like in person. But on an imagination front, it has to be recalled that John Hartnell, as of his father's death, was the eldest male in the household and was holding a massive crown debt in a family that may have had some financial struggle. It's up to a matter of wonder how he felt about his debt, or if he felt the weight of that responsibility that may have influenced his decision to join the Navy at all. For an expedition as widely publicized as Franklin's, it's very possible that the Hartnell brothers signed on for the possibility of financial reprieve. It could have been for adventure as well. Again, it's impossible to know without knowing them, and there's no record to say how they felt or what they were thinking when they made the decision to leave.

The muster book shows 16 shillings (worth about U.S. $55 in 1998 values) deducted from his pay for tobacco, slop (heavy) clothing, and a horsehair mattress. This wasn't much; an experienced sailor, his seabag must have been ready. Offsetting the deductions was two months' advance pay—l0 pounds and 4 shillings (about U.S. $688 today). At a time when a common laborer made 18 pounds a year ($1,210 U.S.), this was quite a windfall.

The paymaster counted the coins out to him at pay parade—ten gold sovereigns and four silver shillings—and by tradition placed them on top of his outstretched cap. Knowing he was bound for three years in the Arctic, with no ports of call or chance to spend it, the money was probably gone before he was—most of it gone on gambling, rounds of gin (a penny a glass), and prostitutes (sixpence for a "knee trembler" in an alley) before sailing.

The fact came down to this; these were two young men in a mid-to-low income family. By the time they left, the muster record shows that John was twenty-five and Thomas was twenty-three. It's another guess of imagination to wonder if they were apprehensive about their joint decision. They were leaving their mother, younger brother, and two younger sisters behind, on a journey that they weren't sure they would return from. This is a moment, a waypoint, where fiction will have to fill in the gaps of fact.

Another question that comes up on that May day in 1845 was if John was yet showing signs of any illness. Evidently, even if he was, it wasn't serious enough to be sent back with several other sailors early on in the voyage. But by the evidence of his autopsy outlined in Frozen in Time, John's health had not always been the best, and recent injuries would have taken a toll.

For this, I had to fill in the gaps with a trusted forensic anthropology instructor and two medical professionals. Again, mysteries came up. The lead poisoning and zinc deficiency controversies were pushed by the wayside for a moment as we went over other details in John's very much posthumous examination. He had osteomyelitis in one foot, meaning an infection in one of his bones. My anthropology instructor suggested that it was very likely that this infection would have spread from his lungs due to the tuberculosis that he ended up succumbing to, as that is a common cause of osteomyelitis in adults. The infection itself spreads through the bloodstream, and although, on its own, the infection in his foot wouldn't have caused him an enormous amount of distress other than some pain, the symptoms on top of that which he already had would have been miserable.

He also had evidence of a compression fracture in his C6 vertebrae, its location shown here for reference.

As this link suggests, his injury might have resulted from a fall while on board, probably onto his back. An injury in his ankle might have been sustained from this possible fall as well. Regardless of what caused the injury, it would have been painful, and eventually very stiff.

The cause of his actual death, however, is far more dismal than any fall or fracture. Tuberculosis, historically, has been viewed as a death sentence. Combined with pneumonia, the possibilities of some lead interference or zinc deficiency, and other symptoms would have made death a slow and painful affair. Although he might have been able to conceal his symptoms at first, as illness on board ships was common, eventually it would have become obvious to the crew that he was too ill to continue working. He had clearly been ill enough for a period of time to cause massive weight loss, which would have been even more obvious on a person who was 5'11", a towering height for the time. It progressed enough that he may have been refusing food--of which the expedition bragged on having enough supplies to last them years--or vomiting so much that he wouldn't have been able to digest it regardless. He would have been feverish, possibly hallucinating, and eventually comatose. Death would have been a relief compared to what John Hartnell went through at the end of his life.

His shipmates appeared to care enough for him to make his last moments presentable. He was dressed from the waist up in multiple layers, including one of Thomas' shirts, and his wool watchcap. His nails may have been cleaned and his hair combed. A pillow was sewn for him, in comparison to the woodshavings that John Torrington rested on. It seemed as though John Hartnell was made to look as presentable as possible, and to appear as he would have as an active AB, dressed from the waist up as if ready for duty.

Although the name plate on his casket was taken by the Inglefield and Sutherland expedition in 1852, it was probably hand hammered as was John Torrington's and William Braine's. As many have postulated, Sir John Franklin, an incredibly religious man, would have taken the chance to hold a funeral for John Hartnell. While not the first sailor to die on the expedition, he was the first of the crew of the Erebus to die. As that was Franklin's ship, that may have carried extra meaning for the captain.

There seems to be a debate as to who performed the infamous inverted autopsy of John Hartnell, with his bizarre upside-down Y incision. Owen Beattie and John Geiger have said that it must have been done by a doctor on the Erebus, possibly physician Henry Goodsir. Ralph Lloyd-Jones says that it was done by Inglefield and Sutherland during their 1852 exhumation that damaged Hartnell's right arm and possibly his right eye. I personally elect to agree with Beattie and Geiger on this point, as although the autopsy seems hurried, I find it much more difficult to think that the 1852 attempt would have taken the time, after hacking through layer upon layer of permafrost, to thaw out John Hartnell, completely undress him, perform the autopsy (mind you, they would have to spend the time to thaw him out down to the organs they clearly removed), sew him back up, redress him, and bury him again, all while fighting the elements using only the protections afforded in 1852. Judging by the condition of his body and clothing when Dr. Beattie's team exhumed him, Inglefield and Sutherland may have taken only the time to dig down to the casket, open it, thaw John out enough to see him and pull his right arm out of the ice, examine his face, and make some hurried deductions based on what they could see and feel. It's still entirely conjecture until more evidence comes up or any further records from 1846 or 1852, but I've at least picked the story I'd like to go with.

The solidity of the facts behind John Hartnell's last days are nothing that is based on record aside from that which was in his autopsy in the 1980s. So much of it is fueled on imagination and prior knowledge of similar cases. To take a step even further away from what can be considered solid fact is to think of what Thomas Hartnell, John's younger brother, went through.

As of now, in 2017, Thomas Hartnell's body has never been found. Although the Erebus and Terror have been discovered to great fanfare and excitement, their crews are still shrouded in mist, so to speak. It's unclear when Thomas died, or how he died, or even where he died. We can't be sure of what his feelings were at his older brother's death, or how he felt about his brother prior. He apparently felt strongly enough about him to give him his shirt, made of a more expensive woven striped fabric, as seen in this photograph.

Based on tradition, Thomas may have been expected to help in funeral preparations, to say some words at the funeral itself, and possibly to put the first shovelful of gravel on his brother's grave. Hundreds of possibilities for thoughts may have gone through his head. He was now the oldest of his siblings, the one responsible for them when (and if) he returned. It may have been a very emotional time for him, having grown up beside John and now knowing he would never see him again. Once again, it's impossible to know how he felt, and how he continued to feel from that moment on Beechey Island to the very end of his life, whenever that occurred.

When it became clear in England that the Franklin Expedition was lost, it's another matter of imagination entirely to know how the Hartnell family felt. Judging by tales from Donald Bray and Brian Spenceley, two descendants of the Hartnells, stories were passed down the line of two brothers who went into the Arctic and didn't return. The family received Thomas' Arctic service medal and his pay, but did not receive John's on account of the crown debt. It wasn't received until January 4th, 1986--one hundred and forty years to the day--to Donald Bray.

While this may seem like a large amount of John's life is recorded (it took me nearly four hours to write this entry), in reality, it's almost nothing. We have his baptism records and that of his siblings, some census records that give us a time and place of residence as well as his career, two muster records from two different ships, evidence of a debt but no evidence of its cause, and the clear and plentiful evidence of his death. His muster records from the Volage say he was 5'11"1/2, with black hair, hazel eyes, and a sallow complexion. His younger brother was fair in appearance, a few inches shorter, freckled, and tattooed on one arm. From what's known, John Hartnell never married and never had children of his own. There's no letters known yet (to me, anyway) of any friends, relationships beyond his family, or anything beyond a very small circle of people. Records and letters may be out there, or they may have very well been lost in the tide, in comparison to documentation of people of greater note than an AB from a small town in Kent.

It's this lack of information that I suppose I found most enticing when I decided to write about John and Thomas. In a life that seems scanty on real hard evidence, there are situations that would have been so ripe with emotion and feeling that as a writer and a historian, it just seems natural to try to explore.

For every time I've tried to discover something more about the brothers and the Hartnell family, more questions come up. It really has been like hide and seek, or like a treasure map with whole sections cut out or faded away. My end goal is this; I want to write a story about this family and these two men in particular that stays as close to the facts as it can, and does so as respectfully and honestly as possible, while still filling in those blanks that I find so enticing. I want John Hartnell's life to become vibrant and real again, to have at least some of the attention paid to John Torrington. And I want to highlight the life of someone comparatively average, like a seaman. Thousands of pages have been paid to people like Franklin, Crozier, Fitzjames, and more. For someone whose occupation was vital to the expedition as well, I feel like it would be a fitting tribute not only to him, not only to the expedition, but to thousands more like John Hartnell, who were in lower positions of ranking, but who lived and died in their line of work. I don't want people like him to be forgotten, or only known for purely macabre reasons (although I do realize the hypocrisy in wanting to write about him due to a picture from his exhumation). If anything, I want to resurrect him, just for a moment, and give him a chance to speak.

Comments

Post a Comment